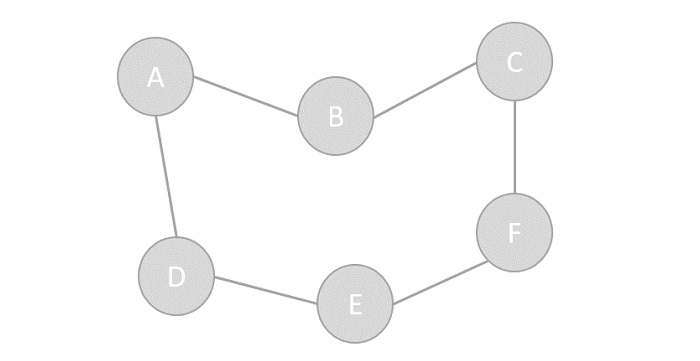

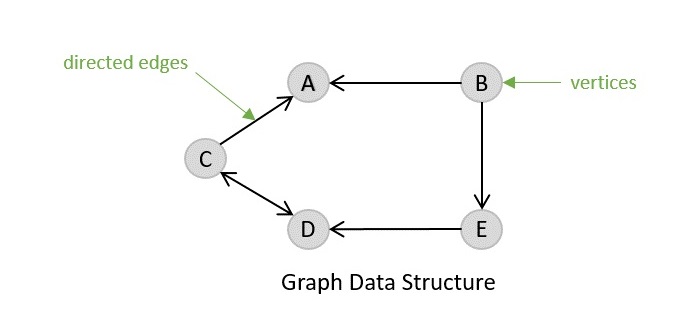

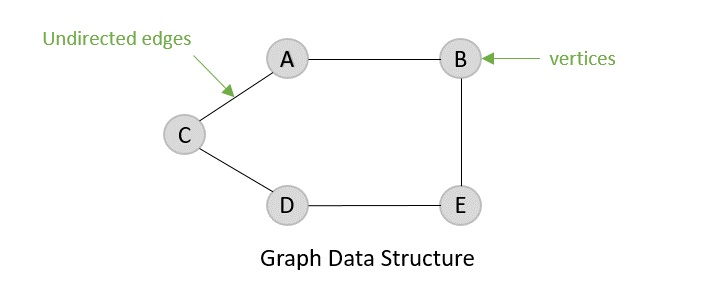

Strongly Connected Components (SCCs) are specific sub-graphs in a directed graph where every node can reach every other node within that sub-graph. In simple terms, SCCs are clusters of nodes that are tightly connected but are separate from other parts of the graph. Understanding SCCs is important, as they help in detecting cycles and studying network structures.

A directed graph is said to be strongly connected if every node can reach every other node directly or indirectly. However, in larger graphs, we may have multiple strongly connected parts that are not connected to each other. These independent sections are called strongly connected components.

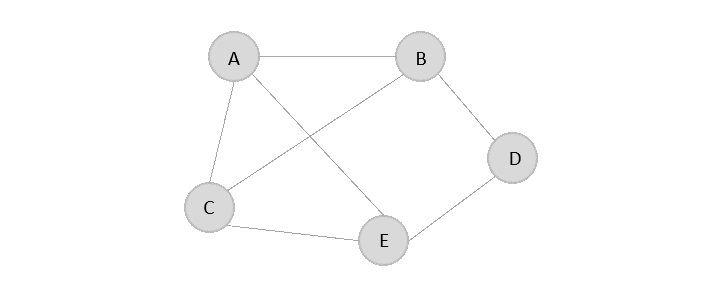

For example, consider a directed graph with nodes A, B, C, D, and E. If A can reach B and B can reach A, but C, D, and E form a separate cluster where they can all reach each other but not A or B, then there are two SCCs in the graph: {A, B} and {C, D, E}.

Strongly Connected Components Algorithm

There are two popular algorithms to find strongly connected components in a graph:

- Kosaraju’s Algorithm

- Tarjan’s Algorithm

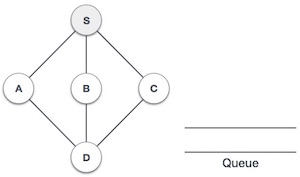

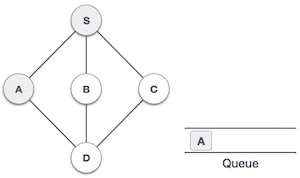

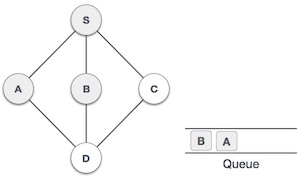

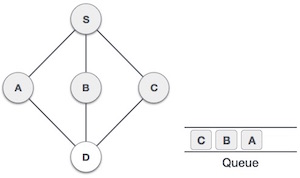

Kosaraju’s Algorithm

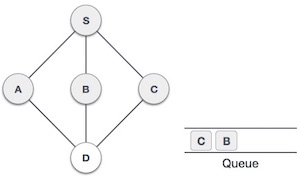

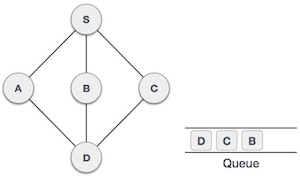

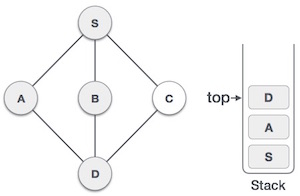

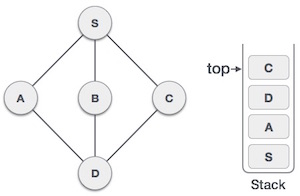

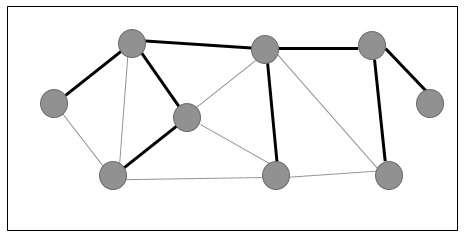

Kosaraju’s Algorithm is a two-pass algorithm that finds strongly connected components in a directed graph. Here’s how it works:

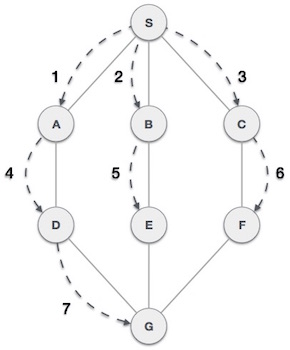

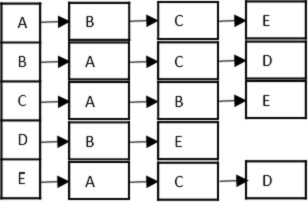

- First Pass: Perform a Depth First Search (DFS) on the graph and store the order of nodes based on their finishing times.

- Second Pass: Reverse the graph and perform another DFS on the nodes in the order of their finishing times from the first pass. This will give us the strongly connected components.

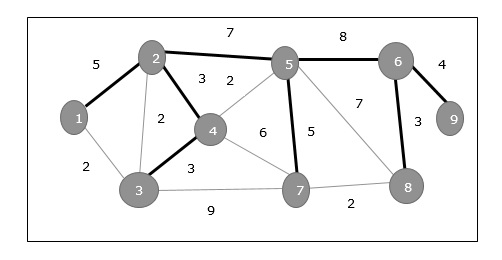

Kosaraju’s Algorithm Example

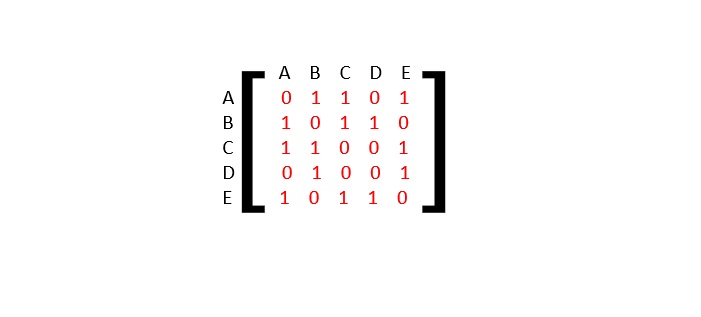

Let’s consider a directed graph with nodes A, B, C, D, and E, and the following edges:

A -> B B -> C C -> A C -> D D -> E E -> D

Using Kosaraju’s Algorithm, we can find the strongly connected components in the graph:

- First Pass: The finishing times of the nodes are E, D, C, B, A.

- Second Pass: The strongly connected components are {A, B, C} and {D, E}.

Code for Kosaraju’s Algorithm

Here’s an example code snippet for Kosaraju’s Algorithm in C, C++, Java, and Python:

#include <stdio.h>#include <stdlib.h>#include <string.h>#define MAX_VERTICES 5// Graph adjacency matrixint adj[MAX_VERTICES][MAX_VERTICES]={{0,1,0,0,0},{0,0,1,0,0},{1,0,0,1,0},{0,0,0,0,1},{0,0,0,1,0}};int visited[MAX_VERTICES]={0};int finishing_time[MAX_VERTICES];int finish_index =0;// Mapping index to letters (A-E)char map[MAX_VERTICES]={'A','B','C','D','E'};voidDFS(int vertex,int print){

visited[vertex]=1;if(print)printf("%c ", map[vertex]);// Print vertex if it's in SCC traversalfor(int v =0; v < MAX_VERTICES; v++){if(adj[vertex][v]&&!visited[v]){DFS(v, print);}}if(!print) finishing_time[finish_index++]= vertex;// Store finishing time if not printing SCC}voidreverse_graph(){int temp[MAX_VERTICES][MAX_VERTICES];for(int i =0; i < MAX_VERTICES; i++){for(int j =0; j < MAX_VERTICES; j++){

temp[i][j]= adj[i][j];}}// Transpose the graphfor(int i =0; i < MAX_VERTICES; i++){for(int j =0; j < MAX_VERTICES; j++){

adj[i][j]= temp[j][i];}}}voidfind_scc(){// Step 1: Compute finishing times in the original graphfor(int v =0; v < MAX_VERTICES; v++){if(!visited[v]){DFS(v,0);// First pass DFS (store finish times)}}// Step 2: Reverse the graphreverse_graph();// Step 3: Second DFS based on decreasing finishing timesmemset(visited,0,sizeof(visited));// Reset visited arrayprintf("Strongly Connected Components:\n");for(int i = MAX_VERTICES -1; i >=0; i--){int vertex = finishing_time[i];if(!visited[vertex]){printf("SCC: ");DFS(vertex,1);// Second pass DFS (print SCC)printf("\n");}}}intmain(){find_scc();return0;}

Output

Following is the output of the above code:

Strongly Connected Components: SCC: A C B SCC: D E

Tarjan’s Algorithm

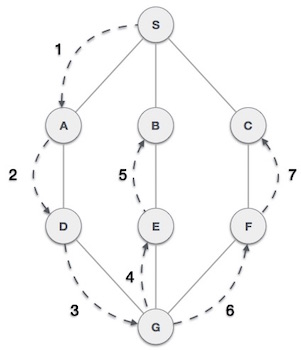

Tarjan’s Algorithm is another popular algorithm to find strongly connected components in a directed graph. It uses Depth First Search (DFS) to traverse the graph and identify SCCs. Here’s how it works:

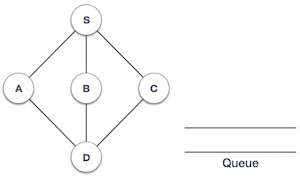

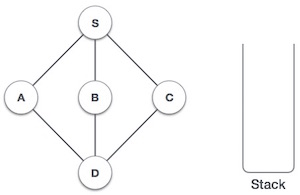

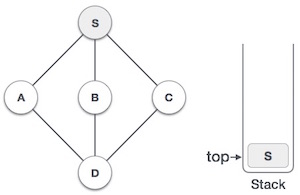

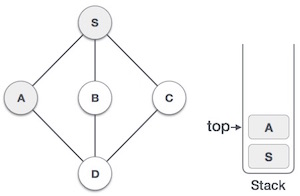

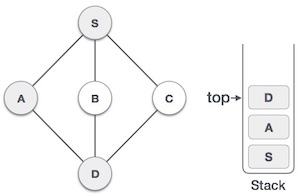

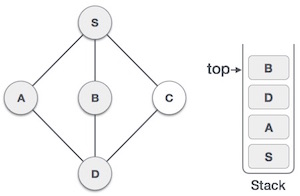

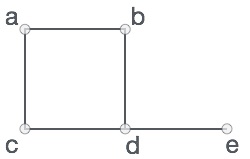

- Initialize a stack to keep track of visited nodes and their order of traversal.

- Perform a DFS traversal of the graph, assigning a unique ID to each node and keeping track of the lowest ID reachable from that node.

- Nodes with the same ID and low-link value form a strongly connected component.

Tarjan’s Algorithm Example

Consider the same directed graph with nodes A, B, C, D, and E, and the following edges:

A -> B B -> C C -> A C -> D D -> E E -> D

Using Tarjan’s Algorithm, we can find the strongly connected components in the graph:

- The strongly connected components are {A, B, C} and {D, E}.

Code for Tarjan’s Algorithm

Here’s an example code snippet for Tarjan’s Algorithm in C, C++, Java, and Python:

#include <stdio.h>#include <stdlib.h>#include <string.h>#define MAX_VERTICES 5// Graph adjacency matrixint adj[MAX_VERTICES][MAX_VERTICES]={{0,1,0,0,0},{0,0,1,0,0},{1,0,0,1,0},{0,0,0,0,1},{0,0,0,1,0}};int visited[MAX_VERTICES]={0};int stack[MAX_VERTICES];int stack_index =0;int ids[MAX_VERTICES];int low[MAX_VERTICES];int id =0;// Mapping index to letters (A-E)char map[MAX_VERTICES]={'A','B','C','D','E'};int map_index =0;voidDFS(int vertex){

stack[stack_index++]= vertex;

visited[vertex]=1;

ids[vertex]= low[vertex]= id++;for(int v =0; v < MAX_VERTICES; v++){if(adj[vertex][v]){if(!visited[v]){DFS(v);}if(ids[v]!=-1){

low[vertex]= low[vertex]0){int node = stack[--stack_index];

low[node]= ids[vertex];printf("%c ", map[node]);if(node == vertex)break;}printf("\n");}}voidfind_scc(){memset(ids,-1,sizeof(ids));memset(low,-1,sizeof(low));for(int v =0; v < MAX_VERTICES; v++){if(!visited[v]){DFS(v);}}}intmain(){find_scc();return0;}

Output

Following is the output of the above code:

SCC: E D SCC: C B A

Applications of Strongly Connected Components

Following are some common applications of Strongly Connected Components:

- Network Analysis: SCCs help in understanding the structure and connectivity of networks, such as social networks, transportation networks, and communication networks.

- Graph Algorithms: SCCs are used in various graph algorithms, such as cycle detection, pathfinding, and network flow optimization.

- Software Engineering: SCCs are useful in software engineering for dependency analysis, module identification, and code refactoring.

Conclusion

Understanding Strongly Connected Components is essential for analyzing the connectivity and structure of directed graphs. Algorithms like Kosaraju’s Algorithm and Tarjan’s Algorithm provide efficient ways to identify SCCs in graphs, enabling various applications in network analysis, graph algorithms, and software engineering.